Introduction

Minangkabau is an indigenous ethnic group and is the world’s largest matrilineal society living in the highlands of West Sumatra, Indonesia. Urang Minangkabau or Minangkabau people have unique and complex socio-religious histories and hierarchies. As a devout Muslim community since the 14th century, the Minangkabau people have their inheritance which is well-known within Indonesia but obscure to most westerners. They share a sense of equality among men and women in the form of social leaders, but in different portions and forms, while the role of Muslim women, to Western eyes, smacks of inequality[1]; they have been represented as homogeneous, submissive, helpless, and oppressed by men. Even so, gender equality for the Minangkabau community is complementary, such male leaders are obliged to control the existence of property (tanah ulayat), and female leaders have the ownership of property[2]. Apart from their formal leaders, i.e., mayor and governor, Minangkabau also has social leaders consisting of Niniak Mamak (male leader), Alim Ulama (religious leaders), Cadiak Pandai (scholars), and Bundo Kanduang (female leader) who represent each social group in the cultural system known as Tungku Tigo Sajarangan. These social leaders have other components, such as Parik Paga (youth leader), but this analysis focuses on the four groups because they are frequently mentioned in research[3] and are actively becoming an influential group in social, political, and religious construction is implemented by the about twentythree tribes in Minangkabau.

In Bukittinggi, Tungku Tigo Sajarangan also holds a vital role in the deliberation process of the development of the Minangkabau community and contributes to the development planning process that still considers the prevailing customs and religious principles which directing the formal leaders’ regulation and policymaking process into practices and society of Minangkabau[4]. The prevailing customs are based on regulations and laws or customary law that apply in the Minangkabau community’s social life and must be found on the religious principle, as an inseparable part of the principle, namely Adat Basandi Syara’ Syara’ Basandi Kitabullah (ABSSBK) or “custom based on religion, and religion based on Qur’an (Islamic holy book),” whereby has become the framework for the Minangkabau philosophy.

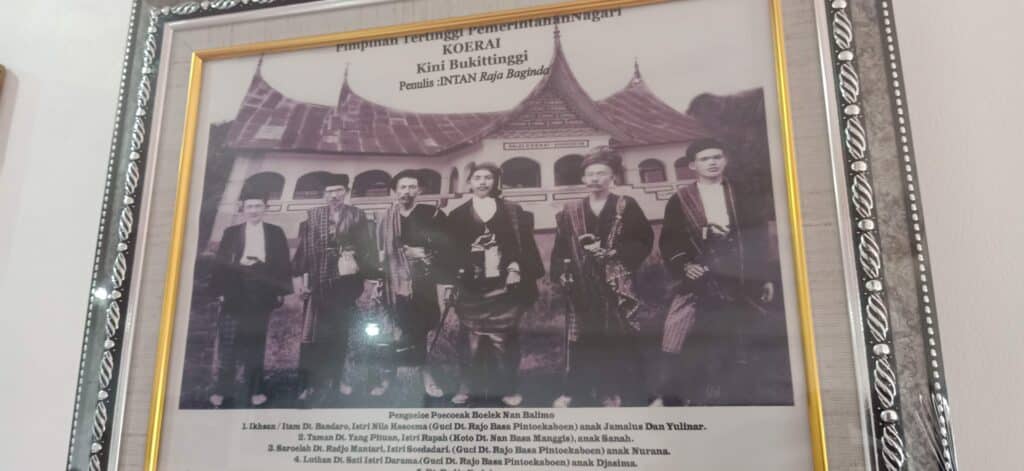

Photo by Intan Raja Baginda of the most important leaders of the Kurai/Koerai Nagari government in Bukittinggi (courtesy of the author, CC BY-NC-SA licence).

Tungku Tigo Sajarangan is divided into several essential components and has roles in the socio-religious Minangkabau community:

- Niniak Mamak (male leader) plays a role in making standard system policies, such as the use of tanah ulayat (inherited land);

- Alim Ulama (religious leaders) play a role in providing socio-religious control to the community based on Islamic values;

- Cadiak Pandai (scholars) play an essential role in the intellectual construction of society, such as laws and regulations, general regulations, so that this group can provide advice and considerations in decision-making;

- Bundo Kanduang (female leader) maintains customary rights and collective property while also ensuring the continuity of education for the next generation.

Aside from customs, culture, and religion, each of these groups plays a role in the movement of the wheels of formal government, either by providing directions, guidelines, guidance, and criticism or by formally running them. In addition, the history of social leaders in Bukittinggi is quite distinct from that of other areas in West Sumatra, where the role of social leaders was previously integrated with the formal government, prior to the Dutch colonial era. This form of government has become distinct but exists in synergistic and contradictory relationships among formal and informal leaders.

Besides, the various roles of this group, both in terms of deliberation and collective decisions, involve not only macro-socio-anthropological elements but also micro-processes, specifically in the neuroanthropology outlook. Lende et al.[5] define neuroanthropology as a synthesis of neuroscience and anthropology that combines cognitive science theories and methods to understand better the interaction of culture, mind, and brain. Neuroanthropology can help fill the gap between the laboratory studies favoured by neuroscience and field-based anthropology focused on sociocultural phenomena. In this study, the focus is on the relationship between culture, customs, society, and each social leader’s brain in Minangkabau in the role she/he takes towards formal leaders. Couser stated that neuroantropology aims to study how culture shapes neurological processes and how neurological substrates may produce distinctive cultural behaviours[6]. As Paredes and Hepburn (1976) stated: “One of the most fundamental intellectual contributions of cultural anthropology is the illumination of the role of cultural patterning in human cognition”.[7]

Furthermore, various studies on the role of social leaders in Minangkabau have not touched the micro field and are still being discussed in a monodisciplinary fashion. Most related research findings demonstrate Tungku Tigo Sajarangan‘s roles and contributions in the sociocultural environment, such as dealing with deviances such as drunkenness, gambling, promiscuity among young people, drugs, criminal acts, and anarchy[8], their active role in the planning process for the social development[9], educating youth morals[10], economic development based on religious principle[11], and so forth. As previously stated, 99.72% (6,8 million) of the Minangkabau population is Muslim[12], so many studies involve their relationship to religious values, norms, and noble culture. The noble values have been taught by the Minangkabau community from generation to generation, particularly in informal education (based on socio-culture and religion), such as how to communicate with friends, respected/older people, and younger people, how to educate children with religious lessons from an early age, how to solve problems through mutual deliberation with communication and increasing good relationship inter-person, and others.

Based on the findings above, research on Minangkabau customs has so far been very limited in comparison to other scientific disciplines, in the form of an interdisciplinary approach, particularly in the field of neuroscience between the brain and social life, where roles, meetings, deliberations, decisions, and policies are taken beginning with the process of brain work. An interdisciplinary approach can provide a systematic, comprehensive theoretical framework for the definition and analysis of the social[13]. The interdisciplinary approach will examine neuroscience and anthropological studies to better understand a social, cultural, or religious group, particularly at Bukittinggi, as one of the intersections between socio-religious practices still exists and lives.

Most Minangkabau people are well-known among other ethnic groups in Indonesia for their progressive thinking. Cadiak Pandai means intelligent and clever, Alim Ulama means knowledgeable and religious, and Bundo Kanduang means biological mother. Uniquely, each of these groups played a significant role in the Indonesian independence process in 1945. It is noted that the Minangkabau people are in the third position in a total of fourteen with the revolutionary leaders[14], the majority of whom are filled by these groups such as Mohammad Hatta, Sutan Sjahrir and Mohammad Natsir[15]. This data demonstrates that Minangkabau’s customs, culture, and religion affect social interaction between social leaders and formal leaders. Audrey Kahin, executive director of the American Institute for Indonesian Studies (AIFIS), praised West Sumatrans for a reputation for being intellectual, clever, and wise[16]. Crawford Young (1979) reports in his book The Politics of Cultural Pluralism that 90 Minangkabau people held Ministerial Officeholders during 1945-1970 in Jakarta, Indonesia. It equates to 14% of all ministry posts or five times the proportion of the ethnic Minangkabau population. Between 2009 and 2014, approximately 14.2%, or up to 80 of the 560 parliamentarians, were Minangkabau[17]. This demonstrates that the Minangkabau people’s thinking ability in both components (formal-social) has significantly contributed to Indonesia’s history up to the present day.

Consequently, this study aims to determine how the brain regulates the role of each social leader in the Minangkabau: Niniak Mamak (male leader), Alim Ulama (religious leaders), Cadiak Pandai (scholars), and Bundo Kanduang (female leader) within the framework of the neuroanthropological discipline. This study is expected to have implications for a better understanding of how the thought processes of Minangkabau social leaders are formed during deliberation and policymaking in social life through policymakers, politicians, and local government. Furthermore, this study is expected to serve as a conceptual framework for implementing studies in a fully naturalistic form, involving neuroscience tools (such as electroencephalograms, brain-computer interfaces, and others), thereby providing a foundation for the government (social and formal leaders) in making decisions and thinking processes.

Methods, Setting Location, and Participants

The author carried out semi-structured interviews for data collection, to determine each community leader’s role, especially one of the Minangkabau tribes, Pasukuan Pisang, in Bukittinggi, West Sumatra, Indonesia. Data analysis was carried out using data reduction, data display, and conclusion drawing. In this study, data reduction referred to selecting and focusing the data on transforming the data from semi-structured interview activities for each participant (social leaders). The data display referred to assembly, organize, and compress data from reduction as the basis for conclusion drawing. Finally, the conclusion drawing referred to the verification of analysis based on the explanation. The data analysis was conducted by coding (extracting the interviews into the research topic and scope)-encoding (explanation and discussion from interviews) on each participant’s interviews with their social or tribal names, as shown in Table 1. The use of participants’ real names (titles or real names) is based on their contribution to the research data findings. Bruckman et al.[18] state that anonymising someone’s name in the research accounts of his/her works would be unethical, considering their accomplishment that deserves credit for their work.

Table 1

Participants and pseudonym

| No. | Social Leaders | Social/Tribal Title or Real Names | Code |

| 1 | Niniak Mamak (male leader) | Inyiak Datuak Sunguik Ameh (social/tribal name) | Inyiak Dt. |

| 2 | Alim Ulama (religious leader) | Malin Bagindo | Malin |

| 3 | Cadiak Pandai (scholar) | Tuanku Tanameh (social/tribal name) | Tk. Tanameh |

| 4 | Bundo Kanduang (female leader) | Rahmiwati (real name) | Rahmiwati |

Findings

The role of social leaders in Bukittinggi

This section will describe the research findings on the role of each social leader in the government in Bukittinggi, West Sumatra and the brain processes that involve ethnic, traditional, regional, and religious interests. This session will present relevant sources from participant interviews about the role of indigenous ethnic leaders as social leaders. The leadership aspect is one of the crucial components involving neuroscience applications, especially in decision-making, with the support of enough information gathered from a variety of biological mechanisms[19]. Minangkabau has two “systems” in place to run the government in West Sumatra, formal government (mayors and governors) and social government (Tungku Tigo Sajarangan).

First, an interview was conducted with one of the Niniak Mamak (male leaders), who first discussed the history of indigenous or social leaders who experienced a shift in roles due to Dutch colonial rule, particularly in Bukittinggi, West Sumatra.

The role of Niniak Mamak in Bukittinggi City has changed since the Dutch colonial period. In the past, Niniak Mamak in Bukittinggi had functional duties, both as social leaders and formal leaders at the government level, said Inyiak Dt.

He explained that Bukittinggi has a unique leadership history. Niniak Mamak’s role in Bukittinggi was dual-functional before Dutch colonialism. This means that a Niniak Mamak’s leadership can occur due to customary norms or because he is also a village or Nagari head, distinct from other areas in Minangkabau. However, he continued, the role of Niniak Mamak changed, and they could no longer carry out dual functions when the wheels of government were handed over to the Dutch during the colonial period and handed back to the Bukittinggi government after Indonesian independence. Hence, the dual-function government was no longer used.

Now, Niniak Mamak’s role with the formal government in Bukittinggi is to consolidate, particularly concerning customary rights or customary land, such as building roads, repairing or building schools, and so on, Inyiak Dt continued.

Niniak Mamak’s role in the government in Bukittinggi is to have complete control over repairs, development, and anything else related to communally owned public facilities (tanah ulayat).

Tanah ulayat is a place where the customary law community (Minangkabau) collectively has the authority and power to enjoy and utilise all natural resources in the area where they live, explained Inyiak Dt.

Apart from dealing with physical forms (Tanah Ulayat), Niniak Mamak has the right to express opinions and views that are still related to the community’s needs in their respective regions (districts) in Bukittinggi. Niniak Mamak’s opinions, points of view, and decisions must be based on recommendations or suggestions from Alim Ulama (religious leaders), which mainly relate to something contradictory, problematic, or that needs explanation regarding culture, education, and heritage land (Tanah Ulayat), that has to be based on Islamic values. Niniak Mamak must first consult with the Alim Ulama, if something is related to Minangkabau’s customary and culturally religious-based principles. However, Alim Ulama’s role in the government is not significant.

Although it is not a large organisation, Alim Ulama has had roles and opportunities in government, particularly in following up on ABSSBK in people’s lives, particularly in the education sector, Malin Bagindo said.

Malin also explained that the role of Alim Ulama focuses on religious-based community activities and education, such as compiling local content-based materials, for instance, the existence of Budaya Alam Minangkabau or Minangkabau Culture in formal education which also collaborating with Cadiak Pandai[20]. Alim Ulama has developing the Islamic religious subject matter in formal, informal, and non-formal education, as well as the formation and preparation of tahfidz programs (the process refers explicitly to a tradition of memorising all 114 surah (chapters) and over 6,000 verses in the Qur’an), and other religious activities.

Furthermore, Cadiak Pandai’s role as an intellectual group can be derived from something other than formal education. This group is on the same level as the previous two social leaders (Niniak Mamak and Alim Ulama). This group comes from a diverse background where they do not have to get a bachelor’s degree, but also come from non-formal and informal education.

Cadiak Pandai has played a key role in the Minangkabau community from the past until now, as evidenced by Mohammad Hatta, Mohammad Yamin, Sutan Syahrir, Haji Agus Salim, Tan Malaka, Syafruddin Prawiranegara, and many others in the process of Indonesia’s independence from Dutch colonialism. This group consists of educated people (coming from not only in formal education, but also informal and non-formal education), who are expected to be able to solve a problem from a different perspective, as previous revolutionary leaders did, said Tk. Tanameh.

According to Tk. Tanameh, Cadiak Pandai’s role in the Bukittinggi government is to provide direction on substantive and implementation issues in the government’s existing regulations.

The government is an essential component in an area. Cadiak Pandai in the Bukittinggi government acts as a policy director, particularly for the common good, under norms and religious rules, and is beneficial in the long and short term, Tk. Tanameh continued.

As a result, Cadiak Pandai’s role in government complements that of Niniak Mamak, Alim Ulama, and Bundo Kanduang, particularly in terms of regulations, policies, and the advancement of science for future generations. In addition, Bundo Kanduang has grown in importance in Minangkabau society. Even though this group has existed since 1833 as a symbol of gender equality in Indonesia, R.A. Kartini is better known in Indonesia as one of the female heroes who served as an icon of justice and equality in 1908. Aside from that, Bundo Kanduang’s role in the Bukittinggi government is diverse, spanning customs, social, educational, and religious matters.

Bundo Kanduang has its program to assist the Bukittinggi government program, in addition to protecting and preserving the heritage of our ancestors in Minangkabau, said Rahmiwati, a member of the Bundo Kanduang group.

She also explained that Bundo Kanduang has a variety of programs.

Bundo Kanduang usually has a meeting schedule that is held at a specific time, usually once a month. The goal is to establish communication relationships and carry out various community-related programs, such as gathering mothers in Bukittinggi, greeting visitors from outside the area, and performing a funeral prayer ritual for those who have died. This activity varies greatly depending on the customs of each region, she explained.

Each of these groups shares common interests to improve the community’s welfare and develop the city and science, so that there are dynamics and the existence of customs and cultures against the times. As a result, each group of Tungku Sajarangan in Bukittinggi has distinct roles and functions in preserving Minangkabau customs and culture based on Islam.

Brain analysis of Minangkabau social leaders from a neuroanthropology outlook

According to the findings above, the role of social leaders in Bukittinggi is closely related to macro processes, particularly Minangkabau culture, and micro processes via brain activity in decision-making, problem-solving, collaboration, and so on. As a result, the relationship between certain cultural phenomena and brain activity can be studied further using neuroanthropology disciplines[21]. Moreover, each Tungku Sajarangan has a unique brain regulation tendency. First, Niniak Mamak plays the role of consolidation and deliberation in providing formal governance direction and advice. Niniak Mamak’s brain works in two directions during this process, ensuring that the communication and advice are beneficial to the community.

On the other hand, Niniak Mamak’s consolidation is expected to reduce losses for both the community and the government. In the cognitive science of decision-making, a decider receives some input (from the senses or memory) and then processes these inputs to arrive at a discrete choice[22]. In this study, the decider is a formal government that receives input from Niniak Mamak to reach a joint decision. Although the input comes from personal senses or memory, in the Minangkabau government system, Niniak Mamak and the formal government must collaborate in decision-making to produce output while minimising losses. The existence of Niniak Mamak serves as a liaison between the government’s and the community’s interests in government and development[23]. For instance, Niniak Mamak in Bukittinggi recently objected to market road infrastructure changes, because they caused community unrest. This refusal is also based on the Minangkabau heritage of roads, which should have preserved traditional values and aesthetics, wherein Niniak Mamak is the leader who has passed down knowledge of Minangkabau customs and culture from generation to generation; they have the duty and will continue to defend the customary land established by their ancestors which remains today[24].

In addition, the consolidation process carried out by Niniak Mamak to the government by considering the interests of the community is one of the regulatory processes of the anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC) in the human brain. aPFC is a region involved in metacognition (the ability to know whether we are right or wrong) that mediates the impact of new evidence on people’s subjective confidence[25], in this case, the Minangkabau society. As a result, Niniak Mamak’s brain in formal government is oriented to concrete policies related to communal affairs while also requiring maximum metacognitive abilities due to the involvement of interested parties.

Second, Alim Ulama is involved in two major fields: education and religion. Alim Ulama tends to rely on religious-based values as absolute sources in the regulatory process. As a result, Alim Ulama’s brain process occurs in two directions: (1) providing opinions, views, and directions to Niniak Mamak in carrying out customary law under religious principles, and (2) planning, developing, and initiating the value of Islam in society. Meanwhile, in a neuroanthropologically outlooks, frontal lobe in the human brain activity has been linked to executive functions such as planning, coordinating movement and behavior, and initiating and producing language[26]. Consequently, the brain processes that occur in Alim Ulama or most religious leaders are dominated by the frontal work lobe of the brain and the activity in the parietal lobes[27]. In general, frontal-parietal circuits have been identified as consistently involved in spiritual and religious experiences in neurological studies of spirituality[28]. For instance, Alim Ulama’s role in informing the people of Bukittinggi not to participate in or celebrate ceremonial events at the end of the year and approaching the new year that is predominantly dominated by young people, such as having sex for unmarried couples, partying, and other anarchic acts that are prohibited in Islam. The regulation of Alim Ulama’s brain in the formal government of Bukittinggi are expected to be dominated by behaviour, personality, and speech via frontal-parietal functions, particularly in determining customary law to conform to Islamic teachings in Minangkabau.

Third, Cadiak Pandai plays a significant role in intellectual thinking, theoretically and practically, especially in regulating policies in the government system, laws, and community policies that are enforced in Bukittinggi. On a neuronal level, higher processing rates and intelligence levels are associated with the brain’s temporal lobe, which generates electrical signals faster[29]. In this process, there is a similarity in the working process of the brain between Alim Ulama and Cadiak Pandai, which are the frontal and parietal regions of the brain. Cadiak Pandai’s brain, in particular, must be capable of providing information to the government promptly and precisely.

Therefore, the intelligence capability of Cadiak Pandai is very much needed, characterized by an effective communication style. At the micro level, the more intelligent people have more strongly involved brain regions in exchanging information between different brain sub-networks for vital information to be communicated rapidly and efficiently[30]. For instance, Cadiak Pandai’s role in developing a Minangkabau education curriculum is based on local wisdom (Budaya Alam Minangkabau/BAM)[31]. Thus, people in the Cadiak Pandai group in Bukittinggi can think quickly and precisely because they are involved in further developing the direction and implementation of government policies.

Finally, Bundo Kanduang’s role in Bukittinggi contributes to developing government programs, particularly women’s empowerment and the continuity of education for the next generation. In a neuroanthropological outlook, the prefrontal cortex of Bundo Kanduang’s brain, controls judgment, decision-making, and consequential thinking, and it develops faster and is larger than in men[32]. This possibility explains Bundo Kanduang‘s role in passing on her leadership from generation to generation, while ensuring the continuity of empowerment in the Minangkabau environment. Bundo Kanduang is known as Limpapeh Rumah Nan Gadang in Minangkabau, which means “pillars” in supporting a building as the role of Bundo Kanduang is to solve social problems in society that are part of the government program itself[33]. In addition, Bundo Kanduang‘s existence of various social programs (such as monthly meeting programs, ceremonial events, and so on) is related to the style of participative leadership styles. It tends to draw more on involvement-oriented[34]. This process is regulated by neural connections between the limbic system and the front part of the brain, allowing them to better manage emotional reactions[35].

The social leaders in Bukittinggi, Minangkabau, have a distinct pattern of leadership tendencies. The distinction arises due to the role of each social group in formal government. Niniak Mamak’s brain’s role is communicating, suggesting, and consolidating common interests, which usually involves metacognition abilities. Alim Ulama and Cadiak Pandai relatively active brains are similar in frontal-parietal circuits, that involve complex thinking abilities, particularly planning and coordination. Besides, Bundo Kanduang‘s brain passed down from generation to generation, accelerated her development by involving the prefrontal cortex and limbic system, both of which play a role in having a good emotional response, particularly in social programs involving many intergenerational people in Bukittinggi.

References

Adya, “Minangkabau In A Nutshell”, Bukunesia Publishing, 2022.

Alfatah, Bukittinggi Selenggarakan Konsolidasi Bundo Kanduang se-Sumatera Barat, in “Antara”, link: https://sumbar.antaranews.com/berita/522861/bukittinggi-selenggarakan-konsolidasi-bundo-kanduang-se-sumatera-barat.

A. Sandoiu, What religion does to your brain, in “Medical News Today”, link: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/322539.

N. Andeska and D. Martion, Tungku Tigo Sajarangan Pada Era Globalisasi Dan Visualisasi Dalam Kriya Seni, in “Bercadik”, IV (2017), 2, link: https://journal.isi-padangpanjang.ac.id/index.php/Bercadik/article/view/571.

A. Rentjoko, Pahlawan terbanyak dari Jateng, Jatim, dan Sumbar. Lokadata.

A. Ardieansyah, I. Meiyenti, E. Mulya Nalien and I. Sentosa, The Role of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan in The Community Development Planning of Minangkabau, Indonesia, in “Transformasi: Jurnal Manajemen Pemerintahan”, 2020, pp. 141–155, link: https://doi.org/10.33701/jtp.v12i2.881

D. Badre, N. A. Goriounova, D. B. Heyer, R. Wilbers, M. B. Verhoog, M. Giugliano, C. Verbist, J. Obermayer, A. Kerkhofs, H. Smeding, M. Verberne, S. Idema, J. C. Baayen, A. W. Pieneman, C. P. De Kock, M. Klein and H. D. Mansvelder, Large and fast human pyramidal neurons associate with intelligence, in “ELIFE”, link: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.41714.001.

H. Basri, M. Ritonga and M. Mursal, The Role of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan in Educating Adolescent Morality through the Indigenous Values of Sumbang Duo Baleh, in “Jurnal Pendidikan”, XIV (2022), 2, pp. 2225-2238, link: https://doi.org/10.35445/alishlah.v14i1.1943.

A. Bruckman, K. Luther and C. Fiesler, When Should We Use Real Names in Published Accounts of Internet Research?, 2002, link: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.htm#46.102.

B. T. Cahya, Optimizing the Development of Islamic Financial Institutions in West Sumatra: Role of Local Wisdom Analysis of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan Mursal, in “Equilibrium: Jurnal Ekonomi Syariah”, VII (2019), 1, pp: 183-202, link: https://journal.iainkudus.ac.id/index.php/equilibrium/article/view/5257.

D. Shapiro, Indonesia’s Minangkabau: The World’s Largest Matrilineal Society, in “Daily Beast”, link: https://www.thedailybeast.com/indonesias-minangkabau-the-worlds-largest-matrilineal-society.

A. M. Dias, The foundations of neuroanthropology. in “Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience”, II (2010), link: https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.18.005.2010.

D. Sofyan, Audrey Kahin: Writing Minangkabau history, in “The Jakarta Post”, link: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/01/22/audrey-kahin-writing-minangkabau-history.html.

H. Khazanah, Ninik Mamak Menolak, Pedagang K5 Berharap.

K. Hilger, M. Ekman, C. J. Fiebach and U. Basten, Intelligence is associated with the modular structure of intrinsic brain networks, in “Scientific Reports”, VII, 1, link: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15795-7.

H. Q. Yousaf and C. A. Rehman, How Neurosciences Effects on Decision Making and Leadership, in “International Review of Management and Business Research”, VI (2017), 1, link: https://www.irmbrjournal.com/paper_details.php?id=627.

B. Johnstone, A. Bodling, D. Cohen, S. E. Christ and A. Wegrzyn, Right Parietal Lobe-Related “Selflessness” as the Neuropsychological Basis of Spiritual Transcendence, in “International Journal for the Psychology of Religion”, XXII, 4, pp. 267-284, link: https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2012.657524.

Joshua Project, Minangkabau in Indonesia. Joshua Project, 2011.

K. Nowack, The Neurobiology of Leadership: Why Women Lead Differently Than Men, 2009, link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253829810.

D. H. Lende, B. I. Casper, K. B. Hoyt and G. L. Collura, Elements of Neuroanthropology, in “Frontiers in Psychology”, XII (2021), link: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.509611.

P. Mason, Brain, Culture and Environment: The Neuroanthropologist and the Self-Accompanied Minangkabau Dancer, in “Jati”, XIII (2008), link: https://jati.um.edu.my/index.php/jati/article/view/6210.

M. Wahyudi, Eksistensi Ninik Mamak dalam Penyelenggaraan Pemerintahan dan Pembangunan di Nagari Sungai Abang Kecamatan Lubuk Alung Kabupaten Padang Pariaman Provinsi Sumatera Barat, in “Institusi Pemerintahan Dalam Negeri”, link: http://eprints.ipdn.ac.id/8726/.

E. Van der Plas, A. S. David and S. M. Fleming, Advice-taking as a bridge between decision neuroscience and mental capacity, in “International Journal of Law and Psychiatry”, LXVII, link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.101504.

P. L. Rosenfield, The Potential Of Transdisciplinary Research For Sustaining And Extending Linkages Between The Health And Social Sciences, in “Sci. Med”, XXXV (1992), pp. 1343-1357, link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1462174/.

S. Bhanbhro, Indonesia’s Minangkabau culture promotes empowered Muslim women, in “The Conversation”, link: https://theconversation.com/indonesias-minangkabau-culture-promotes-empowered-muslim-women-68077.

A. Sayadmansour, Neurotheology: The relationship between brain and religion, in “Iran J Neurol”, XIII, 1, pp. 52-55, link: http://ijnl.tums.ac.ir.

S. Damiano, The Way Women Lead, in “About My Brain”, 2018.

R. Sitompul, A. Alesyanti, H. Hartono and A. Saleh Ahmar, Revitalization Model: The Role of Tigo Tungku Sajarangan in Fostering Character of Children in Minangkabau Family and Its Socialization Through Website, in “International Journal of Engineering & Technology”, VII (2018), 2, pp. 53-57, link: www.sciencepubco.com/index.php/IJET.

U. Baste, Smarter People Have Better Connected Brains, in “Neuroscience News”, 2017.

Yus, Melalui Pendidikan BAM di SD dan SMP, Pemko Bukittinggi Akan Terapkan Pelestarian Adat Minangkabau, in “Berita Minang”, 2022, link: https://www.beritaminang.com/berita/17274/melalui-pendidikan-bam-di-sd-dan-smppemko-bukittinggi-akan-terapkan-pelestarian-adat-minangkabau.html.

Y. Garand, Women in Leadership: The Power of the Female Brain, in “Empowering Possibilities”, link: https://www.vsecu.com/blog/women-in-leadership-the-power-of-the-female-brain/.

[1] D. Shapiro, Indonesia’s Minangkabau: The World’s Largest Matrilineal Society, in “Daily Beast”, link: https://www.thedailybeast.com/indonesias-minangkabau-the-worlds-largest-matrilineal-society.

[2] S. Bhanbhro, Indonesia’s Minangkabau culture promotes empowered Muslim women, in “The Conversation”, link: https://theconversation.com/indonesias-minangkabau-culture-promotes-empowered-muslim-women-68077.

[3] N. Andeska and D. Martion, Tungku Tigo Sajarangan Pada Era Globalisasi Dan Visualisasi Dalam Kriya Seni, in “Bercadik”, IV (2017), 2, link: https://journal.isi-padangpanjang.ac.id/index.php/Bercadik/article/view/571; A. A. Ardieansyah, I. Meiyenti, E. Mulya Nalien and I. Sentosa, The Role of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan in The Community Development Planning of Minangkabau, Indonesia, in “Transformasi: Jurnal Manajemen Pemerintahan”, 2020, pp. 141–155, link: https://doi.org/10.33701/jtp.v12i2.881; H. Basri, M. Ritonga and M. Mursal, The Role of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan in Educating Adolescent Morality through the Indigenous Values of Sumbang Duo Baleh, in “Jurnal Pendidikan”, XIV (2022), 2, pp. 2225-2238, link: https://doi.org/10.35445/alishlah.v14i1.1943; B. T. Cahya, Optimizing the Development of Islamic Financial Institutions in West Sumatra: Role of Local Wisdom Analysis of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan Mursal, in “Equilibrium: Jurnal Ekonomi Syariah”, VII (2019), 1, pp: 183-202, link: https://journal.iainkudus.ac.id/index.php/equilibrium/article/view/5257; R. Sitompul, A. Alesyanti, H. Hartono and A. Saleh Ahmar, Revitalization Model: The Role of Tigo Tungku Sajarangan in Fostering Character of Children in Minangkabau Family and Its Socialization Through Website, in “International Journal of Engineering & Technology”, VII (2018), 2, pp. 53-57, link: www.sciencepubco.com/index.php/IJET.

[4] E. Mulya Nalien, I. Meiyenti and I. Sentosa, The Role of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan in The Community Development Planning of Minangkabau, Indonesia, in “Transformasi: Jurnal Manajemen Pemerintahan”, XII (2020), 2, pp. 141-155, link: https://doi.org/10.33701/jtp.v12.i2.881.

[5] D. H. Lende, B. I. Casper, K. B. Hoyt and G. L. Collura, Elements of Neuroanthropology, in “Frontiers in Psychology”, XII (2021), link: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.509611.

[6] P. Mason, Brain, Culture and Environment: The Neuroanthropologist and the Self-Accompanied Minangkabau Dancer, in “Jati”, XIII (2008), link: https://jati.um.edu.my/index.php/jati/article/view/6210.

[7] P. Mason, Brain, Culture and Environment: The Neuroanthropologist and the Self-Accompanied Minangkabau Dancer, in “Jati”, XIII (2008), link: https://jati.um.edu.my/index.php/jati/article/view/6210.

[8] N. Andeska and D. Martion, Tungku Tigo Sajarangan Pada Era Globalisasi Dan Visualisasi Dalam Kriya Seni, in “Bercadik”, IV (2017), 2, link: https://journal.isi-padangpanjang.ac.id/index.php/Bercadik/article/view/571.

[9] Ardieansyah, I. Meiyenti, E. Mulya Nalien and I. Sentosa, The Role of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan in The Community Development Planning of Minangkabau, Indonesia, in “Transformasi: Jurnal Manajemen Pemerintahan”, 2020, pp. 141–155, link: https://doi.org/10.33701/jtp.v12i2.881.

[10] H. Basri, M. Ritonga and M. Mursal, The Role of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan in Educating Adolescent Morality through the Indigenous Values of Sumbang Duo Baleh, in “Jurnal Pendidikan”, XIV (2022), 2, pp. 2225-2238, link: https://doi.org/10.35445/alishlah.v14i1.1943; R. Sitompul, A. Alesyanti, H. Hartono and A. Saleh Ahmar, Revitalization Model: The Role of Tigo Tungku Sajarangan in Fostering Character of Children in Minangkabau Family and Its Socialization Through Website, in “International Journal of Engineering & Technology”, VII (2018), 2, pp. 53-57, link: www.sciencepubco.com/index.php/IJET.

[11] B. T. Cahya, Optimizing the Development of Islamic Financial Institutions in West Sumatra: Role of Local Wisdom Analysis of Tungku Tigo Sajarangan Mursal, in “Equilibrium: Jurnal Ekonomi Syariah”, VII (2019), 1, pp: 183-202, link: https://journal.iainkudus.ac.id/index.php/equilibrium/article/view/5257.

[12] Joshua Project, Minangkabau in Indonesia. Joshua Project, 2011.

[13] P. L. Rosenfield, The Potential Of Transdisciplinary Research For Sustaining And Extending Linkages Between The Health And Social Sciences, in “Sci. Med”, XXXV (1992), pp. 1343-1357, link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1462174/.

[14] A. Rentjoko, Pahlawan terbanyak dari Jateng, Jatim, dan Sumbar. Lokadata.

[15] D. Sofyan, Audrey Kahin: Writing Minangkabau history, in “The Jakarta Post”, link: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/01/22/audrey-kahin-writing-minangkabau-history.html.

[16] D. Sofyan, Audrey Kahin: Writing Minangkabau history, in “The Jakarta Post”, link: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/01/22/audrey-kahin-writing-minangkabau-history.html.

[17] A. Adya, “Minangkabau In A Nutshell”, Bukunesia Publishing, 2022.

[18] A. Bruckman, K. Luther and C. Fiesler, When Should We Use Real Names in Published Accounts of Internet Research?, 2002, link: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.htm#46.102.

[19] H. Q. Yousaf and C. A. Rehman, How Neurosciences Effects on Decision Making and Leadership, in “International Review of Management and Business Research”, VI (2017), 1, link: https://www.irmbrjournal.com/paper_details.php?id=627.

[20] Yus, Melalui Pendidikan BAM di SD dan SMP, Pemko Bukittinggi Akan Terapkan Pelestarian Adat Minangkabau, in “Berita Minang”, 2022, link: https://www.beritaminang.com/berita/17274/melalui-pendidikan-bam-di-sd-dan-smppemko-bukittinggi-akan-terapkan-pelestarian-adat-minangkabau.html.

[21] A. M. Dias, The foundations of neuroanthropology. in “Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience”, II (2010), link: https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.18.005.2010.

[22] E. Van der Plas, A. S. David and S. M. Fleming, Advice-taking as a bridge between decision neuroscience and mental capacity, in “International Journal of Law and Psychiatry”, LXVII, link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.101504.

[23] M. Wahyudi, Eksistensi Ninik Mamak dalam Penyelenggaraan Pemerintahan dan Pembangunan di Nagari Sungai Abang Kecamatan Lubuk Alung Kabupaten Padang Pariaman Provinsi Sumatera Barat, in “Institusi Pemerintahan Dalam Negeri”, link: http://eprints.ipdn.ac.id/8726/.

[24] H. Khazanah, Ninik Mamak Menolak, Pedagang K5 Berharap.

[25] E. Van der Plas, A. S. David and S. M. Fleming, Advice-taking as a bridge between decision neuroscience and mental capacity, in “International Journal of Law and Psychiatry”, LXVII, link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.101504.

[26] A. Sayadmansour, Neurotheology: The relationship between brain and religion, in “Iran J Neurol”, XIII, 1, pp. 52-55, link: http://ijnl.tums.ac.ir.

[27] A. Sandoiu, What religion does to your brain, in “Medical News Today”, link: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/322539.

[28] B. Johnstone, A. Bodling, D. Cohen, S. E. Christ and A. Wegrzyn, Right Parietal Lobe-Related “Selflessness” as the Neuropsychological Basis of Spiritual Transcendence, in “International Journal for the Psychology of Religion”, XXII, 4, pp. 267-284, link: https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2012.657524.

[29] D. Badre, N. A. Goriounova, D. B. Heyer, R. Wilbers, M. B. Verhoog, M. Giugliano, C. Verbist, J. Obermayer, A. Kerkhofs, H. Smeding, M. Verberne, S. Idema, J. C. Baayen, A. W. Pieneman, C. P. De Kock, M. Klein and H. D. Mansvelder, Large and fast human pyramidal neurons associate with intelligence, in “ELIFE”, link: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.41714.001.

[30] K. Hilger, M. Ekman, C. J. Fiebach and U. Basten, Intelligence is associated with the modular structure of intrinsic brain networks, in “Scientific Reports”, VII, 1, link: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15795-7; U. Baste, Smarter People Have Better Connected Brains, in “Neuroscience News”, 2017.

[31] Yus, Melalui Pendidikan BAM di SD dan SMP, Pemko Bukittinggi Akan Terapkan Pelestarian Adat Minangkabau, in “Berita Minang”, 2022, link: https://www.beritaminang.com/berita/17274/melalui-pendidikan-bam-di-sd-dan-smppemko-bukittinggi-akan-terapkan-pelestarian-adat-minangkabau.html.

[32] Y. Garand, Women in Leadership: The Power of the Female Brain, in “Empowering Possibilities”, link: https://www.vsecu.com/blog/women-in-leadership-the-power-of-the-female-brain/.

[33] Alfatah, Bukittinggi Selenggarakan Konsolidasi Bundo Kanduang se-Sumatera Barat, in “Antara”, link: https://sumbar.antaranews.com/berita/522861/bukittinggi-selenggarakan-konsolidasi-bundo-kanduang-se-sumatera-barat.

[34] K. Nowack, The Neurobiology of Leadership: Why Women Lead Differently Than Men, 2009, link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253829810.

[35] S. Damiano, The Way Women Lead, in “About My Brain”, 2018.